Design for the long tail

Don't overdesign

In the requirements phase, you defined a clear set of key use cases. Keep these priorities in mind and avoid adding edge cases to this list. As you get into the details of the design, new scenarios will come up that you hadn’t considered. Before expanding the scope of the design to handle these new scenarios, carefully consider the impact.

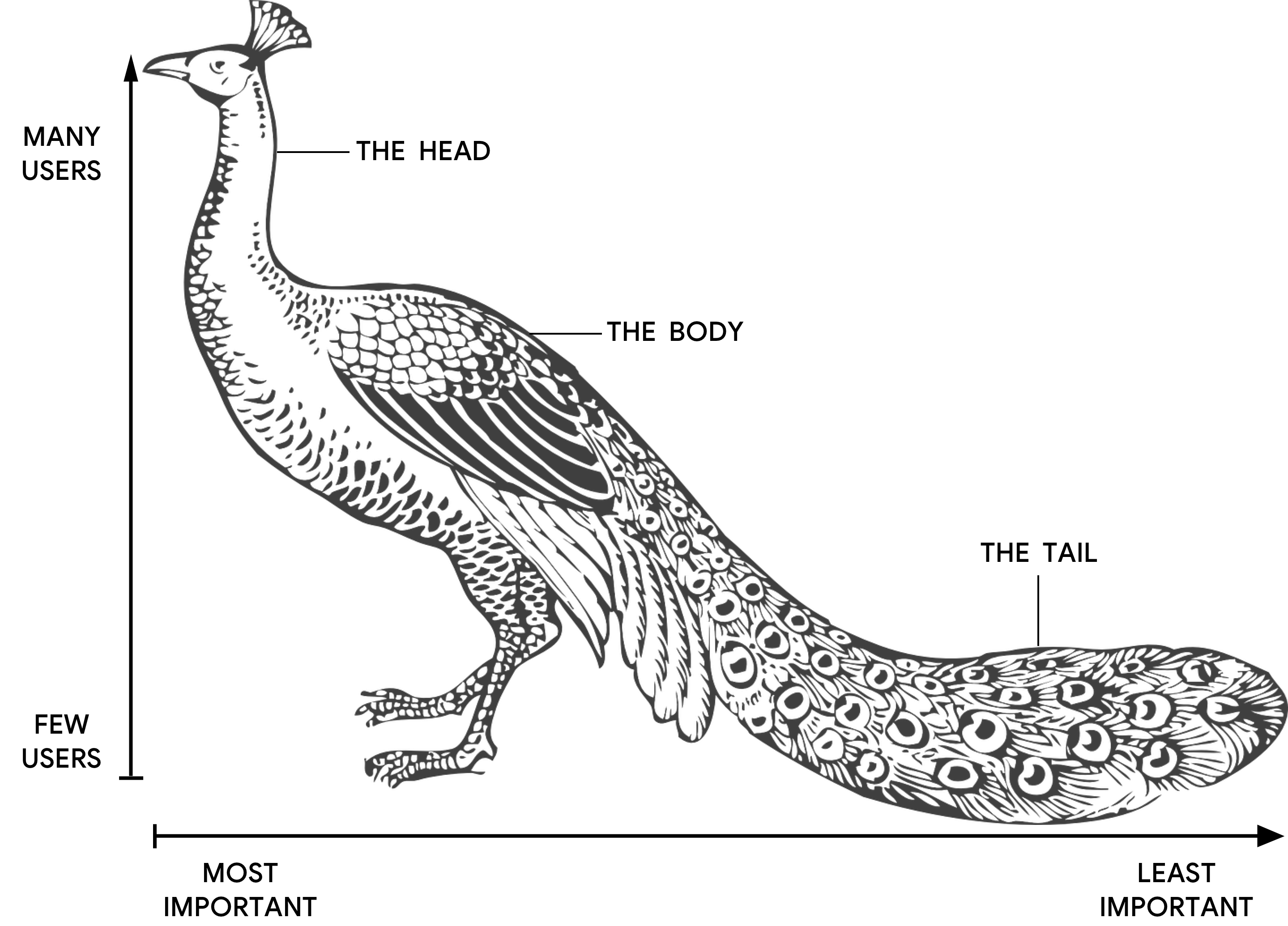

| The head | The body | The long tail |

|---|---|---|

|

Key use cases These are the most important and most common conversational paths that users will take through your feature. Focus the majority of your effort on making these paths a great user experience. |

Detours These are less common, and often less direct or less successful, conversational paths through your feature. Take the time to adequately support them, but avoid spending too much time and effort designing them. |

Edge cases These are highly uncommon paths. Consider whether generic prompts like “Sorry I’m not sure how to help” are good enough, or if you can be a little more specific with a similar minimally viable solution. |

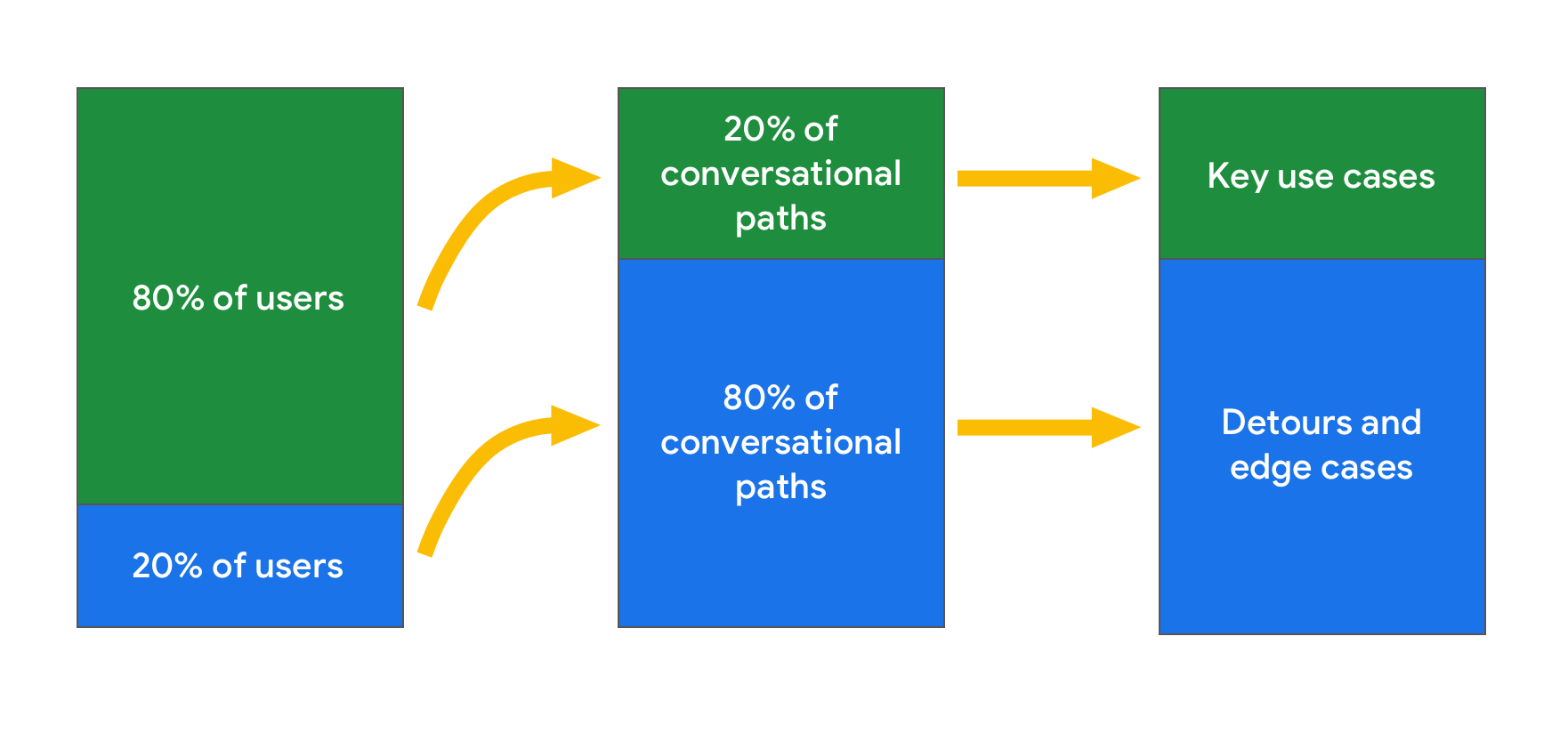

Use the 80/20 rule, or Pareto Principle, to avoid overdesigning.

For conversation design, this rule is a way of saying that not all paths are created equal. 80% of users follow the most common 20% of possible paths in a dialog. Therefore, invest resources accordingly for the biggest impact.

Similarly, there are trade-offs in terms of perfection or completeness. It may take 80% of the work to really polish the last 20% of the project. In these cases, the unpolished effort may be "good enough."

Common detours

In between key use cases and edge cases are a number of somewhat common detours. Usually, these are new scenarios that you hadn’t considered until they were revealed during testing or discovered during development. And most of the time, they require longer, less direct handling down an alternative path.

Here’s a couple of common detours to consider:

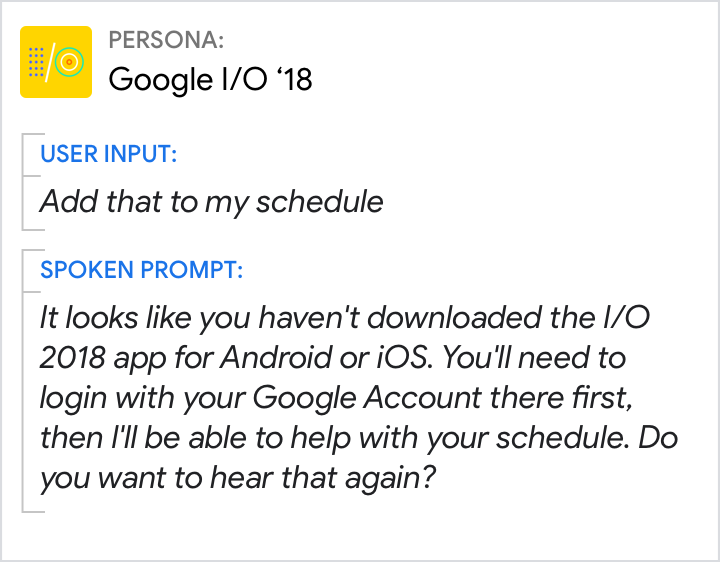

Unlinked accounts

In this case, the user has not linked their account.

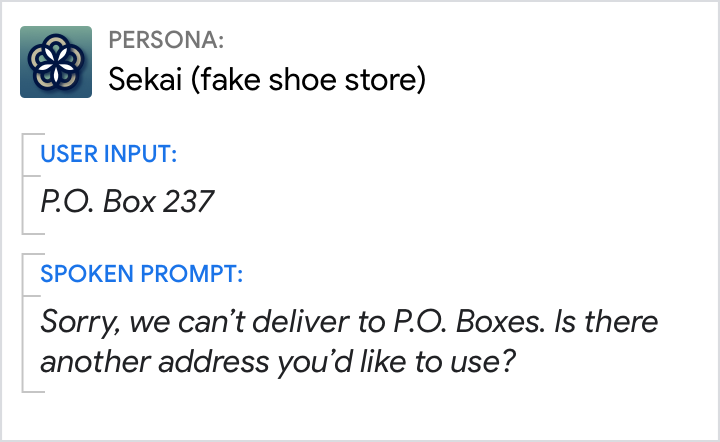

Unsupported actions

Users may ask for actions that your Action can’t support.

Intent coverage

Conversation design involves scripting one half of a dialog, hoping it’s robust enough that anyone can step in and act out the other half. When designing for the long tail, focus on what the user could say at every step in your dialog to define your intents (also called grammars).

An intent represents a mapping between what a user says and what your Action should do as a result. For example, the prompt “Do you like pizza?” requires intents for “yes” and “no”. Each intent should have a variety of training phrases associated with it, including synonyms like “yeah” and “nope” as well as variations like “I love it” or “It’s gross.” These may be weighted by how frequently they occur. Intents can also include annotation, for example, categorizing “fresh mozzarella” as a pizza topping in the user response “only if it’s made with fresh mozzarella.”

If you’re using Dialogflow, go here to read more about intents.

Preventing errors from occurring is better than handling errors after they occur.

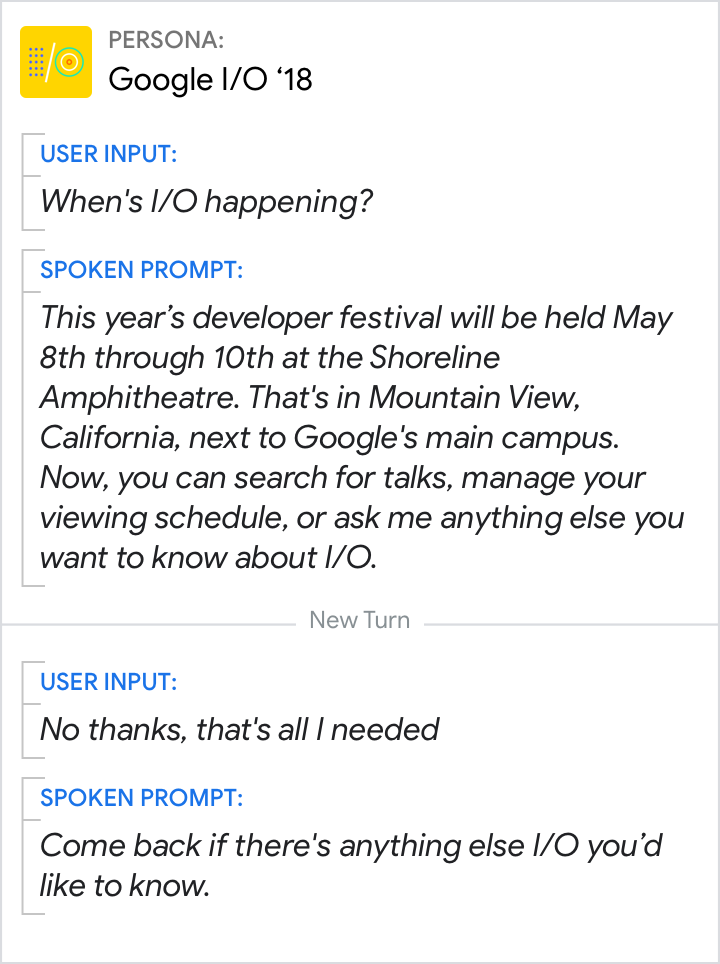

Do.

Include a “done” intent with training phrases like “I’m done” or “that’s all."

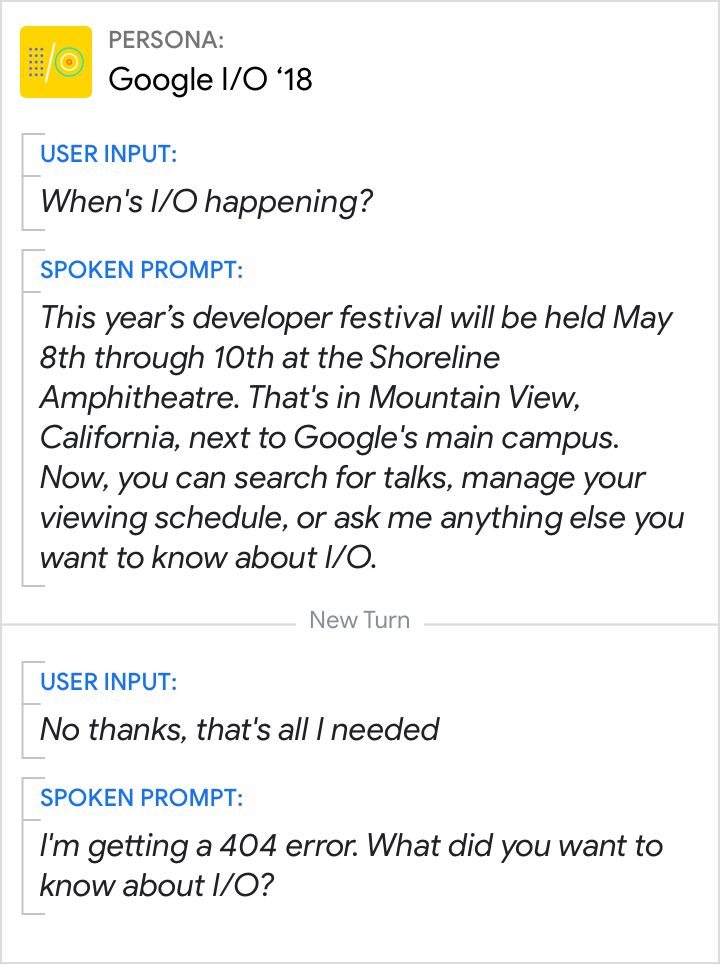

Don't.

If the Action is only expecting questions about I/O, the user’s response will trigger a No Match error.

Error handling

Even with robust intents, there is still room for error. Users may go off script by remaining silent (a No Input error) or saying something unexpected (a No Match error). Use error prompts to gently steer users back towards successful paths or reset their expectations about what is and isn’t possible.

Good error handling is context-specific, so prompts for No Input and No Match errors must be designed for every turn in the dialog.