지금까지 공정성 측정항목에 대한 논의는 학습이 테스트 예제에는 인구통계에 대한 포괄적인 인구통계 데이터가 포함되어 있습니다. 하위 그룹이 있습니다. 하지만 그렇지 않은 경우가 많습니다.

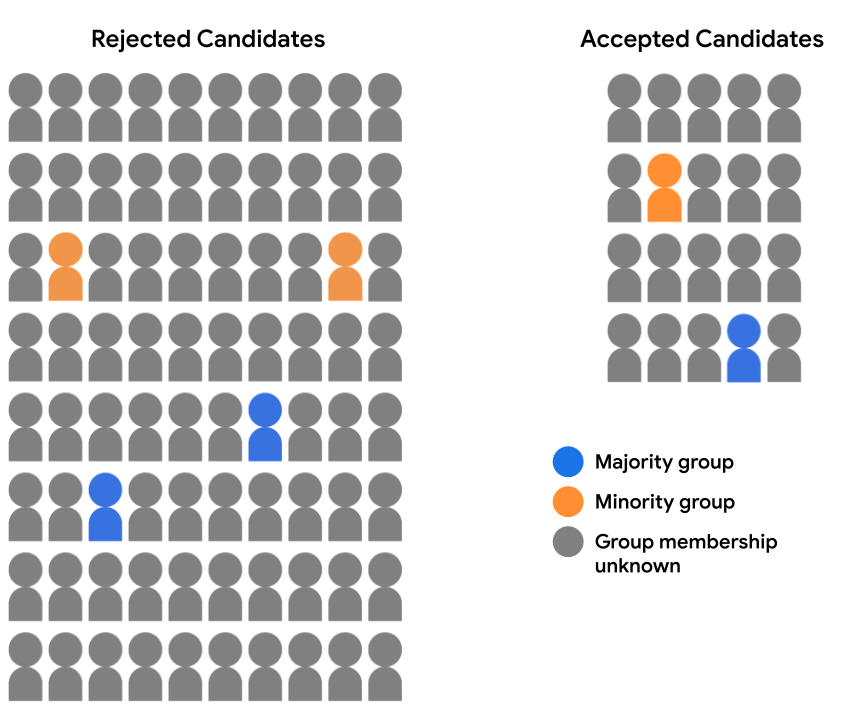

입학 데이터 세트에 완전한 인구통계 데이터가 포함되어 있지 않다고 가정해 보겠습니다. 대신 일부 인구통계 그룹 멤버십은 자신이 속한 그룹을 스스로 밝히기로 선택한 학생 등 예 볼 수 있습니다 이 경우 지원자 풀을 허용됨으로 분류하여 그러면 다음과 같이 표시됩니다.

두 인구통계에 대한 모델 예측을 평가하는 것은 불가능합니다. 인구통계 데이터가 없기 때문에 기회의 동등성 또는 기회의 균등 94% 에 이르렀습니다 그러나 개별 예측값의 쌍을 비교할 수 있으므로 과반수 후보자 대다수의 후보자를 비교하여 모델에 의해 공평하게 취급되어야 합니다.

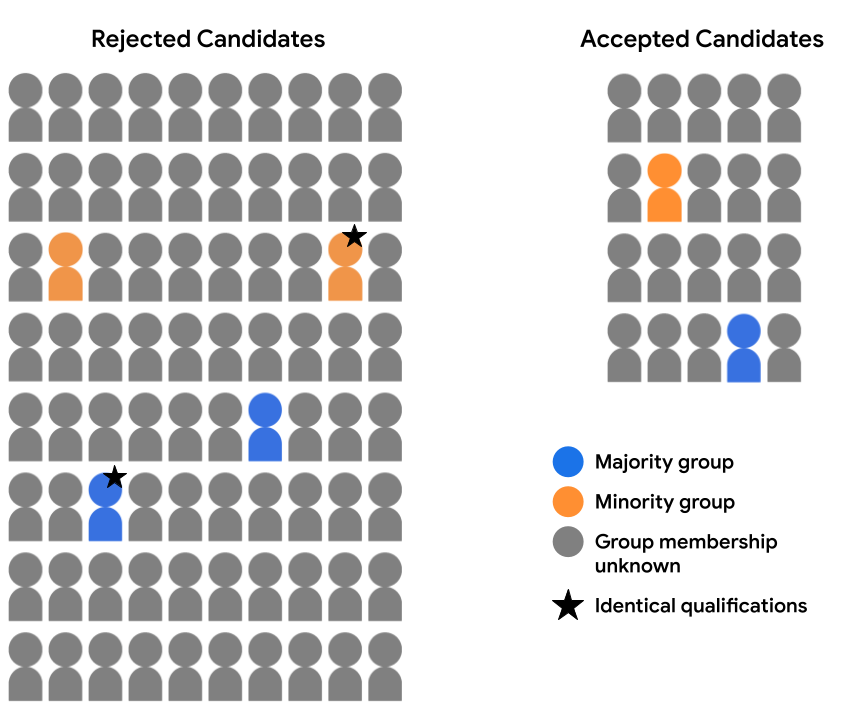

예를 들어 특성 데이터를 철저히 검토했다고 가정해 보겠습니다. 2명의 후보 (다수 집단 및 소수 집단 1개)에게 제공됨 별표 주석이 달린 그룹이 있음)를 실행하여 모든 면에서 동일하게 입학 자격이 주어집니다. 모델이 두 후보 모두에 대해 동일한 예측을 수행 (즉, 둘 다 거부함) 두 가지 모두를 수락하는 경우)는 반사실적인 경우 공정성을 평가합니다. 반사실적 공정성은 특정 민감한 속성을 제외하고 모든 면에서 동일한 예 (여기에서는 인구통계 그룹 멤버십)이 동일한 모델 을 얻습니다. 학습합니다.

장단점

앞서 언급했듯이 반사실적 공정성의 한 가지 주요 이점은 공정성 예측을 평가하는 데 다른 측정항목은 실현할 수 없습니다. 데이터 세트에 데이터 세트의 전체 집합이 포함되지 않은 경우 특성 값을 고려하는 경우 해당 그룹 속성에는 인구통계 동등성 또는 인구 평등을 사용하여 공정성을 평가할 수 있습니다. 그러나 이러한 그룹 속성을 유사한 문장을 찾아낸다는 점에서 실무자들은 반사실적 공정성 모델을 사용하여 모델을 사용하여 예측의 잠재적 편향을 탐색하기 위한 측정항목으로 사용할 수 있습니다

또한 인구통계 동등성과 동등성과 같은 측정항목이 기회는 그룹을 종합하여 평가하므로, 영향을 미치는 편향 문제를 은폐할 수 있습니다 개별 예측 수준에서 모델을 학습시킬 수 있으며, 이는 반사실적 공정성을 사용하여 평가합니다. 예를 들어 입학 허가가 다수 집단과 소수 집단에서 적합한 후보를 수용함 속한 집단이지만 가장 자격을 갖춘 소수 집단 후보는 가장 자격을 갖춘 과반수 후보자가 사용자 인증 정보가 허용됩니다 반사실적 공정성 분석은 이러한 종류의 불일치를 해결하여 해결할 수 있습니다.

반면에 반사실적 공정성의 주요 단점은 모델 예측의 편향을 전체적으로 파악할 수 있습니다. 식별 및 예시 쌍으로 소수의 불평등을 해결하는 것만으로는 충분하지 않을 수 있습니다. 전체 하위 그룹에 영향을 미치는 시스템적 편향 문제를 해결합니다.

가능한 경우 실무자는 두 가지를 모두 집계하여 공정성 분석 (인구통계 동등성 또는 반사실적 공정성 분석을 사용하여 광범위한 인사이트를 제공합니다

연습문제: 학습 내용 점검하기

<ph type="x-smartling-placeholder">

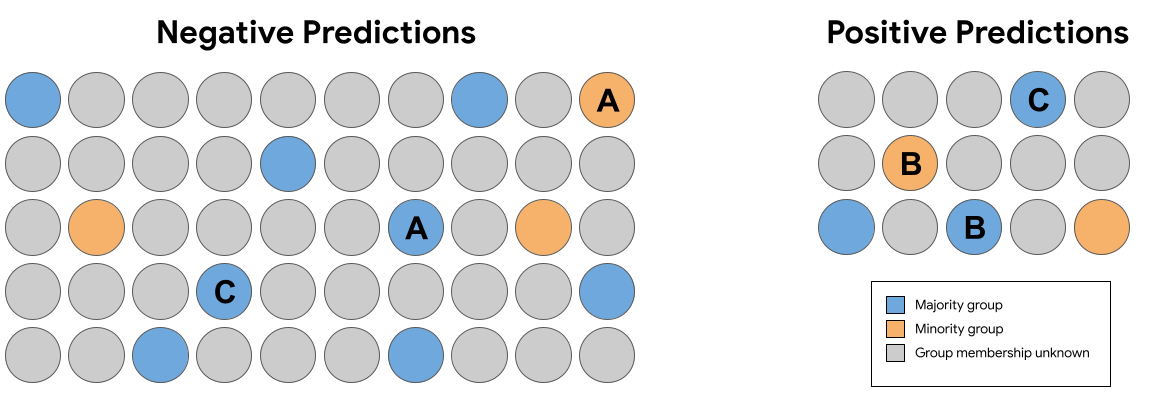

<ph type="x-smartling-placeholder">위 그림 7의 예측 세트에서 다음 동일한 쌍 (그룹 구성원 제외) 반사실적 공정성을 위반하는 예측을 받은 사례가 있습니까?

요약

인구통계 동등성 기회의 평등, 반사실적 공정성과 반사실적 공정성은 각각 다른 수학적 정의를 공정성을 유지해야 합니다 이 세 가지 옵션은 공정성을 정량화하는 방법을 배웠습니다. 공정성에 대한 일부 정의는 서로 상호 간에 호환되지 않음 즉, 일정 시간 동안 여러 번 동시에 충족시키는 것이 불가능할 수 예측하기 위한 것입니다.

그렇다면 '적절한' 옵션을 선택하는 방법은 공정성 측정항목을 사용해야 할까요? 해야 할 일 데이터가 사용되는 상황과 고려해야 할 중요한 목표를 있습니다. 예를 들어 모든 사람이 동일한 대표성을 달성한다는 목표를 달성하기 위해 (이 경우 인구통계 동등성이 최적의 측정항목일 수 있습니다) 아니면 기회의 균등( 측정항목)?

ML 공정성에 대해 자세히 알아보고 이러한 문제를 더 자세히 알아보려면 다음을 참조하세요. 솔론 바로카스, 모리츠 하트, 아르빈드 나라야난의 공정성과 머신러닝: 한계와 기회