2011年5月19日星期四

发表者:Gary Illyes,Webmaster趋势分析师(Trends Analyst)

原文: Website Security for Webmasters

用户们都被教育通过安装复杂的杀毒软件来保护自己免受恶意程序的侵扰,但是通常他们还可能将私人信息委托给您这样的网站,这时保护他们的数据就变得十分重要。而保护您自己的数据也非常关键;如果您有一个在线商店,您可不希望它遭到洗劫。

多年来,公司和网站站长们认识到——通常是在经过艰难的体验后——网络应用程序安全并非儿戏;我们曾见证过由于 SQL注入 攻击而使用户密码泄漏、通过跨站脚本 XSS 使cookie失窃,以及由于输入验证的疏忽而使网站被黑客控制。

现在我们将向您展示一些例证,说明如何充分利用网络应用程序从而学到一些方法;为此我们将使用 Gruyere ,这是一款我们用来进行内部安全训练的、专门设置的应用程序。请不要在未经允许的情况下探测他人的网站寻求漏洞,因为这可能被认为是黑客攻击;但是欢迎——不,是鼓励您——在Gruyere上进行相应的测试。

客户状态控制 – 如果我修改URL将会发生什么?

假设您有一个图片主机站点并且您使用PHP script来显示用户上传的图片:

https://www.example.com/showimage.php?imgloc=/garyillyes/kitten.jpg

如果我将URL修改成这样并且userpasswords.txt是一个实际的文件,那么该应用程序将会怎么做?

https://www.example.com/showimage.php?imgloc=/../../userpasswords.txt

我会取得userpasswords.txt的内容吗?

客户状态控制的另一个例证是当表单域无效时。例如,假设您有这样的表单:

看起来提交人的用户名存储在一个隐藏的输入域。这样就太好了!这是否意味着如果将那个域的值修改为另一个用户名,我就能作为该用户提交表单了呢?这种情况很可能会发生;用户输入显然没有获得证明,例如一个能够在服务器上核实的令牌。

请想象这样一种情况,如果那份表单是您购物车的一部分,而我将一件1000美元的商品价格修改成了1美元,之后提交订单。

保护您的应用程序免受此类攻击的侵扰并非易事;请参看 Gruyere的第三部分 ,学习几条如何保护您应用程序的小技巧。

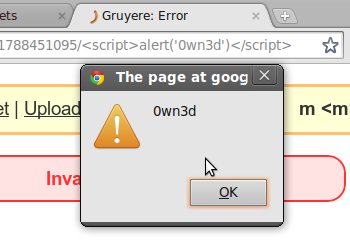

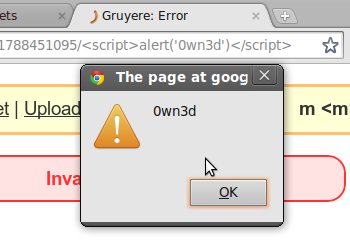

跨站脚本(XSS)- 用户输入无法被信任

一个简单、无害的URL:

https://google-gruyere.appspot.com/611788451095/%3Cscript%3Ealert('0wn3d')%3C/script%3E

但它真的是无害的吗?如果我将 百分比编码字符 解码,我将得到:

<script>alert('0wn3d')</script>

与很多带有 自定义错误页面 的网站一样,Gruyere专门包含了HTML页面中的路径组件。这可以引起安全错误,例如XSS,因为它将用户输入直接引入到了网络应用程序的已渲染HTML页面。您可能会说,“这只是个警告框,又能怎么样?”问题是,如果我能引入一个警告框,我就很可能也能引入其他东西,并且可能盗取能够用来以您的身份登入您网站的cookie。

另一例证是当储存的用户输入未经审查时。假设我在您的博客上写下一条评论;评论很简单:

<a href=”javascript:alert(‘0wn3d’)”>Click here to see a kitten</a>

如果其他用户点击我的无害链接,我就有了他们的cookie:

在 Gruyere的第二部分 ,您可以学习如何在您自己的网络应用程序中寻找XSS漏洞以及如何修复它们;或者,如果您是一位高级开发者,那就请参看我们在 在线安全博客 上发表的关于模板系统中的自动转义功能博文。

跨站伪造请求(XSRF)- 我是否应该信任来自evil.com的请求?

哎呀,一个断开的图片。这不会构成危险——毕竟它断开了——这意味着该图片的URL返回了一个404或仅仅是格式错误。那么所有情况下都如此吗?

不,绝非如此!您可以指定任何URL作为图片源,不论其内容类型。它可以是一个HTML页面、一个JavaScript文件,或某些其他潜在的恶意源。在这种情况下,图片源就是一个简单页面的URL:

该页面仅在我登录并且设置了某些cookie时起作用。由于我实际登录了应用程序,因此当浏览器试图通过进入图片源URL获取图片时,它同时删除了我的首个片断。这听起来不是很危险,但是如果我对应用程序有一点熟悉,我还可以请求一个能够删除用户信息或使管理员为其他用户授予权限的URL。

为了保护您的应用程序免遭XSRF的侵害,您不应当允许通过GET来要求更改状态的活动;POST方法的发明就是为了应对此种状态更改请求。这一更改本身可能能够减轻以上的攻击,但是通常这并不够,您还需要在所有状态更改请求中包含一个不可预测的值来防范XSRF。如果您希望了解更多有关XSRF的知识,请查询 Gruyere 。

跨站脚本包含(XSSI)- 您所有的脚本都是我们的

现在很多网站都能通过可以返回JSON数据的异步JavaScript请求动态更新页面内容。有时,JSON能够包含敏感数据,而如果没有正确的预防措施,那么很可能攻击者就能盗取此敏感信息。

让我们想象一下以下的情境:我创建了一个标准HTML页面并给您发送了链接;由于您很信任我,您就访问了我发送的链接。该页面仅包括几行内容:

<script>function _feed(s) {alert("Your private snippet is: " + s['private_snippet']);}</script><script src="https://google-gruyere.appspot.com/611788451095/feed.gtl"></script>

由于您登入到了Gruyere并且您有一个私人片断,您将在我的页面看到一个警告框,告知您有关您片断的内容。如往常一样,如果我设法启动一个警告框,我就能为所欲为;在这里,它仅是一个简单的片断,但是它也很可能是您最大的秘密。

防御您的应用程序不受XSSI的危害并不十分困难,但仍然需要谨慎的思考。您可以使用XSRF部分所解释的令牌、将您的脚本设置为仅回应POST请求,或简单地开启带有‘\n’的JSON响应以确保脚本无法执行。

SQL注入 – 仍然认为用户输入很安全吗?

如果我试图使用如下的用户名登入您的应用程序,将会发生什么?

无名氏’; 删除表成员;--(JohnDoe’; DROP TABLE members;--)

虽然这个具体的例证不会暴露用户数据,但由于它可能将您应用程序储存有成员信息在其上的SQL表完全移除,因此还是能造成很大的问题。

通常,您可以通过主动思考和输入确认来保护您的应用程序免受SQL注入的侵害。首先,您是否能确认SQL用户需要拥有许可来执行“DROP TABLE members”吗?仅授予选择权限不是足够了吗?通过谨慎设置SQL用户的许可,您可以避免遭受痛苦的困扰和大量的麻烦。您还可以以另外一种方式配置错误报告,这样如果查询失败,则数据库和它的表的名字将不会遭到暴露。

第二,正如我们在XSS情形中所了解到的,永远都不要信任用户输入:对您来说看起来像是登陆表格的,对攻击者来说就是一个潜在的入口。对于即将储存在数据库中的输入,永远要进行审查和确认,并且在任何可能的情况下,要利用在大多数数据库编程接口都能获取的、被称为有准备的或被参数化的声明。

了解网络应用程序如何得到利用是理解如何保护它们的第一步。因此,我们鼓励您参加 Gruyere课程 、参加其他来自 Google编程学院 的网络安全课程,并且,如果您正需要一款自动的网络应用程序安全测试工具的话,不妨试试 skipfish 。如果您还有其他问题,请在我们的 网站站长帮助论坛 发帖提出。

原文: Website Security for Webmasters

用户们都被教育通过安装复杂的杀毒软件来保护自己免受恶意程序的侵扰,但是通常他们还可能将私人信息委托给您这样的网站,这时保护他们的数据就变得十分重要。而保护您自己的数据也非常关键;如果您有一个在线商店,您可不希望它遭到洗劫。

多年来,公司和网站站长们认识到——通常是在经过艰难的体验后——网络应用程序安全并非儿戏;我们曾见证过由于 SQL注入 攻击而使用户密码泄漏、通过跨站脚本 XSS 使cookie失窃,以及由于输入验证的疏忽而使网站被黑客控制。

现在我们将向您展示一些例证,说明如何充分利用网络应用程序从而学到一些方法;为此我们将使用 Gruyere ,这是一款我们用来进行内部安全训练的、专门设置的应用程序。请不要在未经允许的情况下探测他人的网站寻求漏洞,因为这可能被认为是黑客攻击;但是欢迎——不,是鼓励您——在Gruyere上进行相应的测试。

客户状态控制 – 如果我修改URL将会发生什么?

假设您有一个图片主机站点并且您使用PHP script来显示用户上传的图片:

https://www.example.com/showimage.php?imgloc=/garyillyes/kitten.jpg

如果我将URL修改成这样并且userpasswords.txt是一个实际的文件,那么该应用程序将会怎么做?

https://www.example.com/showimage.php?imgloc=/../../userpasswords.txt

我会取得userpasswords.txt的内容吗?

客户状态控制的另一个例证是当表单域无效时。例如,假设您有这样的表单:

看起来提交人的用户名存储在一个隐藏的输入域。这样就太好了!这是否意味着如果将那个域的值修改为另一个用户名,我就能作为该用户提交表单了呢?这种情况很可能会发生;用户输入显然没有获得证明,例如一个能够在服务器上核实的令牌。

请想象这样一种情况,如果那份表单是您购物车的一部分,而我将一件1000美元的商品价格修改成了1美元,之后提交订单。

保护您的应用程序免受此类攻击的侵扰并非易事;请参看 Gruyere的第三部分 ,学习几条如何保护您应用程序的小技巧。

跨站脚本(XSS)- 用户输入无法被信任

一个简单、无害的URL:

https://google-gruyere.appspot.com/611788451095/%3Cscript%3Ealert('0wn3d')%3C/script%3E

但它真的是无害的吗?如果我将 百分比编码字符 解码,我将得到:

<script>alert('0wn3d')</script>

与很多带有 自定义错误页面 的网站一样,Gruyere专门包含了HTML页面中的路径组件。这可以引起安全错误,例如XSS,因为它将用户输入直接引入到了网络应用程序的已渲染HTML页面。您可能会说,“这只是个警告框,又能怎么样?”问题是,如果我能引入一个警告框,我就很可能也能引入其他东西,并且可能盗取能够用来以您的身份登入您网站的cookie。

另一例证是当储存的用户输入未经审查时。假设我在您的博客上写下一条评论;评论很简单:

<a href=”javascript:alert(‘0wn3d’)”>Click here to see a kitten</a>

如果其他用户点击我的无害链接,我就有了他们的cookie:

在 Gruyere的第二部分 ,您可以学习如何在您自己的网络应用程序中寻找XSS漏洞以及如何修复它们;或者,如果您是一位高级开发者,那就请参看我们在 在线安全博客 上发表的关于模板系统中的自动转义功能博文。

跨站伪造请求(XSRF)- 我是否应该信任来自evil.com的请求?

哎呀,一个断开的图片。这不会构成危险——毕竟它断开了——这意味着该图片的URL返回了一个404或仅仅是格式错误。那么所有情况下都如此吗?

不,绝非如此!您可以指定任何URL作为图片源,不论其内容类型。它可以是一个HTML页面、一个JavaScript文件,或某些其他潜在的恶意源。在这种情况下,图片源就是一个简单页面的URL:

该页面仅在我登录并且设置了某些cookie时起作用。由于我实际登录了应用程序,因此当浏览器试图通过进入图片源URL获取图片时,它同时删除了我的首个片断。这听起来不是很危险,但是如果我对应用程序有一点熟悉,我还可以请求一个能够删除用户信息或使管理员为其他用户授予权限的URL。

为了保护您的应用程序免遭XSRF的侵害,您不应当允许通过GET来要求更改状态的活动;POST方法的发明就是为了应对此种状态更改请求。这一更改本身可能能够减轻以上的攻击,但是通常这并不够,您还需要在所有状态更改请求中包含一个不可预测的值来防范XSRF。如果您希望了解更多有关XSRF的知识,请查询 Gruyere 。

跨站脚本包含(XSSI)- 您所有的脚本都是我们的

现在很多网站都能通过可以返回JSON数据的异步JavaScript请求动态更新页面内容。有时,JSON能够包含敏感数据,而如果没有正确的预防措施,那么很可能攻击者就能盗取此敏感信息。

让我们想象一下以下的情境:我创建了一个标准HTML页面并给您发送了链接;由于您很信任我,您就访问了我发送的链接。该页面仅包括几行内容:

<script>function _feed(s) {alert("Your private snippet is: " + s['private_snippet']);}</script><script src="https://google-gruyere.appspot.com/611788451095/feed.gtl"></script>

由于您登入到了Gruyere并且您有一个私人片断,您将在我的页面看到一个警告框,告知您有关您片断的内容。如往常一样,如果我设法启动一个警告框,我就能为所欲为;在这里,它仅是一个简单的片断,但是它也很可能是您最大的秘密。

防御您的应用程序不受XSSI的危害并不十分困难,但仍然需要谨慎的思考。您可以使用XSRF部分所解释的令牌、将您的脚本设置为仅回应POST请求,或简单地开启带有‘\n’的JSON响应以确保脚本无法执行。

SQL注入 – 仍然认为用户输入很安全吗?

如果我试图使用如下的用户名登入您的应用程序,将会发生什么?

无名氏’; 删除表成员;--(JohnDoe’; DROP TABLE members;--)

虽然这个具体的例证不会暴露用户数据,但由于它可能将您应用程序储存有成员信息在其上的SQL表完全移除,因此还是能造成很大的问题。

通常,您可以通过主动思考和输入确认来保护您的应用程序免受SQL注入的侵害。首先,您是否能确认SQL用户需要拥有许可来执行“DROP TABLE members”吗?仅授予选择权限不是足够了吗?通过谨慎设置SQL用户的许可,您可以避免遭受痛苦的困扰和大量的麻烦。您还可以以另外一种方式配置错误报告,这样如果查询失败,则数据库和它的表的名字将不会遭到暴露。

第二,正如我们在XSS情形中所了解到的,永远都不要信任用户输入:对您来说看起来像是登陆表格的,对攻击者来说就是一个潜在的入口。对于即将储存在数据库中的输入,永远要进行审查和确认,并且在任何可能的情况下,要利用在大多数数据库编程接口都能获取的、被称为有准备的或被参数化的声明。

了解网络应用程序如何得到利用是理解如何保护它们的第一步。因此,我们鼓励您参加 Gruyere课程 、参加其他来自 Google编程学院 的网络安全课程,并且,如果您正需要一款自动的网络应用程序安全测试工具的话,不妨试试 skipfish 。如果您还有其他问题,请在我们的 网站站长帮助论坛 发帖提出。